My New Blue House in Crete

Living in old Turkish hammam in Halepa

MAY 2, 2025 | CHANIA | 23 MIN

MAY 2, 2025 | CHANIA | 23 MIN

My New Blue House in Crete

Living in old Turkish hammam in Halepa

Halepa in 1907. View from the terrace of the former French Consulate to the east.

Free will is an illusion. Many of the most famous places of human existence on Earth were not chosen consciously by man - they were somehow imposed on him from the outside: sometimes the horse pulling the cart did not want to go any further, sometimes someone had a dream with a revelation that this is where he should build a city, and many places of religious worship were chosen because someone heard the voice of the Lord. Man does not decide where, man reads the signs.

It was the same with my new home in Crete. I was not looking for a new place, it just came to me. My friend Petro acted as the messenger revealing the signs. He told me that an apartment had become available in his building and I might want to see it. Interestingly, the interior did not impress me at all, but while viewing it, the owner casually mentioned that there was another apartment up for grabs in the same building. This time I had no doubts, this could be my place.

Crete, Chania, Halepa

My new home in Crete is located in Chania, in the eastern part of the city, in the Halepa district. Almost on top of a hill, overlooking the sea, although I can’t see much from my windows. The northern coast of the island is 500 m as the crow flies, and the coast of the Libyan Sea in the south is about 35 km away. Our Cretan “highway” connecting cities on the northern coast also runs quite close by, and in an hour I can reach Kissamos in the west, and in three hours Agios Nikolaos in the east. From the point of view of my daily activities, it is important to note that I am only 6 kilometers away from the foot of the nearest real mountain (500 meters high) in Nerokourou, so I can easily get there by bike. To give you an idea of the scale of the island, I will also mention that from my home I can run across the whole of Crete from north to south in one day, even if Pachnes (2453) – the highest peak of Lefka Ori (White Mountains) – is on the way. Such a route is about 70 km long and has 3000 meters of elevation gain. The White Mountains remain my primary place of exploration and that is why I chose Chania as the place to live a few years ago.

The so-called “aristocratic” buildings in Halepa. From left: High Commissioner’s Palace (in ruins), English Consulate (now a hotel), Eleftheris Vanizelos House (museum).

Halepa yesterday and today

Halepa used to be considered an aristocratic district, located outside the city walls, a little further from the centre, on the hills. Today, it is difficult to feel any aristocratic atmosphere here, although when I return home along the once main street of Halepa, I do indeed pass the buildings of four former consulates of the great powers (at the beginning of the 20th century, Crete was an autonomous state with its capital in Chania – hence the consulates), the palace of the High Commissioner Prince George (the most beautiful of them all, unfortunately abandoned) and the house of Eleftherios Venizelos – one of the most distinguished Greek politicians of the early 20th century, who was born in Crete and lived here for many years.

Contemporary Halepa is a mosaic of new apartment buildings, historical structures from different periods and… ruins. As everywhere in Greece, ruins are omnipresent in my district. These include entire buildings, abandoned relatively recently, because their shape is still easy to recognize, and with a little effort they could be brought back to life, houses without roofs and walls, which have long since lost their original shape, and assigning them to a particular style and historical period is already very difficult, and scattered here and there ancient probably foundations (which in Crete could mean a period of three and a half thousand years) since no one has dared to completely dismantle them and build something new in this place.

After all, Halepa is still a rather wild district, with a somewhat rural atmosphere, full of steep ravines, abandoned olive groves, orange orchards and cactus thickets. Due to this wild landscape – and well-kept gardens – Halepa is very green. Buildings from different historical periods shimmer with shades of beige, brown and sometimes even pink, the ruins are an intense ochre color.

Veli Pasha's house from 1852

What was hammam in Islam?

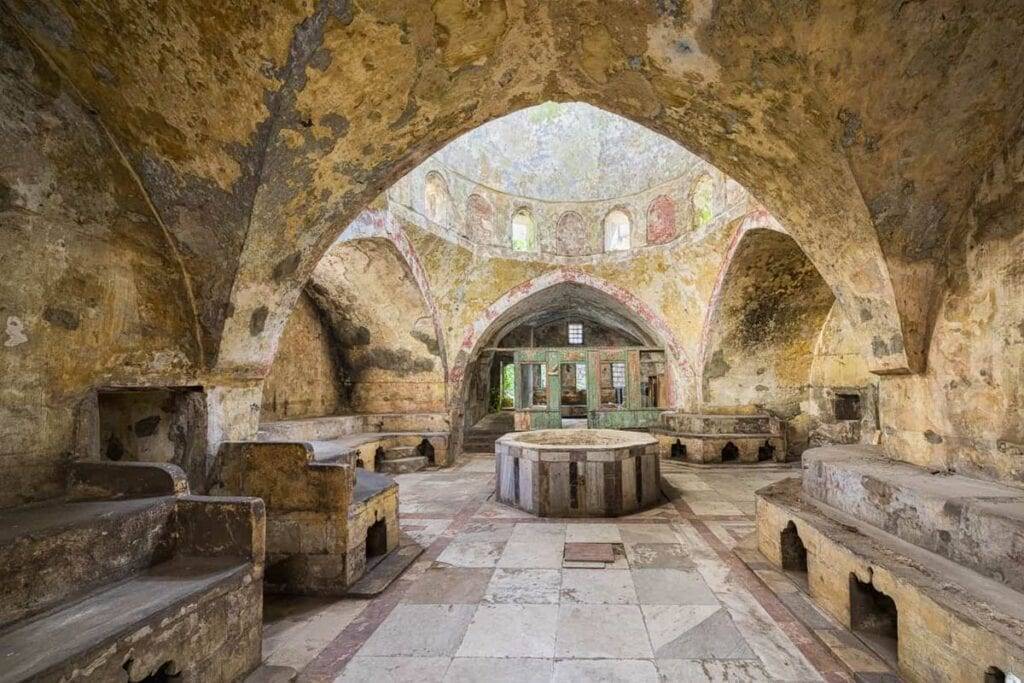

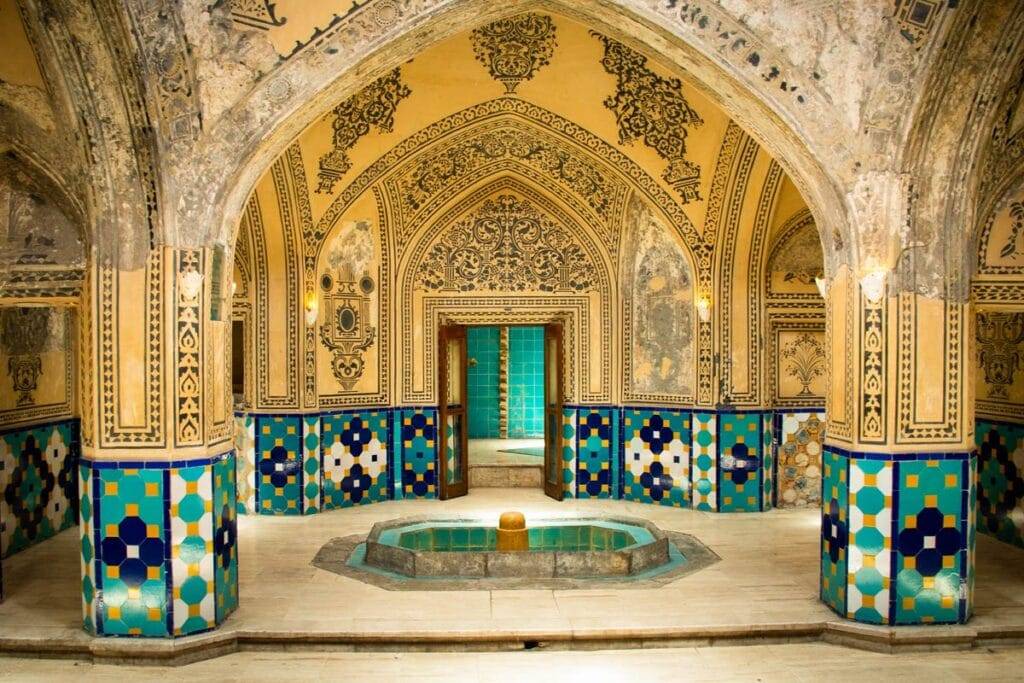

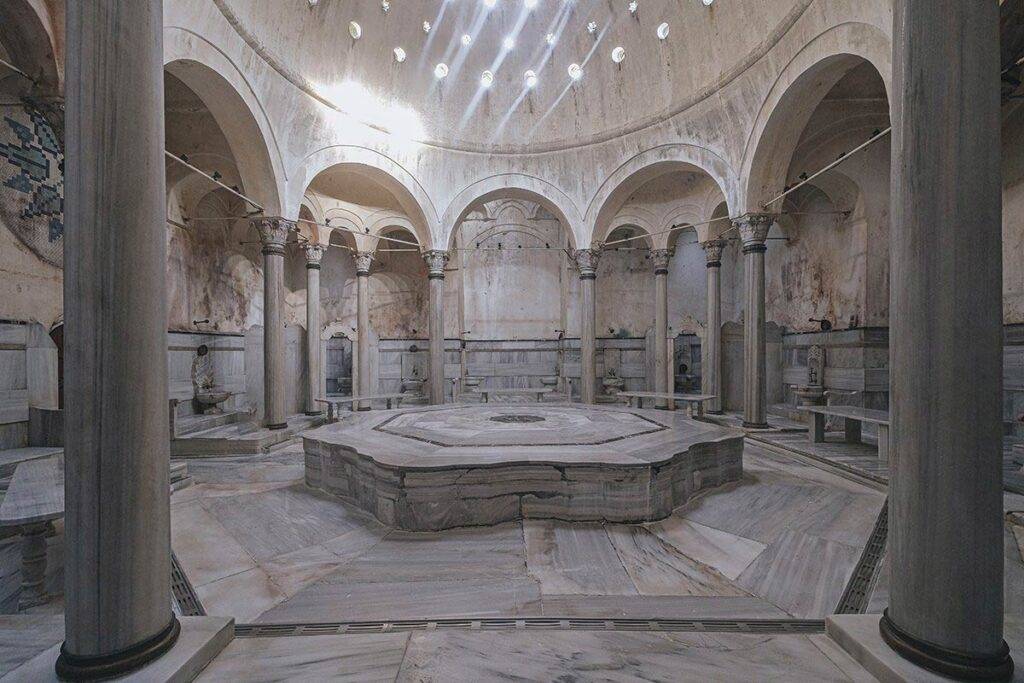

Hammams in the Islamic world were often funded by rulers and were richly decorated. The photo on the right shows a characteristic semicircular vault with holes for releasing water vapor. From the left: Hammam Al-Nouri, Lebanon; Sultan Amir Ahmad Hammam, Kashan, Iran; Cagaloglu Hammam Stambul.

Reading the signs of the past

The hammam that once existed in my current apartment was of course not public; it was part of a private residence, but because the residence was quite large, my interior exceeds the size of even large bathrooms in the most comfortable modern villas. I am trying to imagine what this hammam used to look like, and thanks to this I can better understand the current appearance of my studio. A small attempt at exercises in imaginary archeology.

The ceiling of my “apartment” is flat and concrete, with clearly imprinted patterns of wooden planks, serving as a temporary base. However, most hammams had domed vaults, with small holes (sometimes in the shape of stars) to release excess water vapour. The ceiling is almost certainly much more modern than the rest, especially since my upstairs neighbour has a terrace on my roof. Even in the smallest hammams there was a separate room where there was a large furnace for heating water and air, which was piped to the main part. And indeed such a small annex is located next to my apartment, although there is no furnace there anymore. If my hammam was really comfortable, it is easy to explain why my interior is very high (4m) and you go down a few steps to it. Well, real hammams had heated floors – some of the hot air was directed to special channels placed under the floor. The channels of course took up some space, and if all the structures in the floor were removed in the modern times, the level dropped by a good half a meter. My two large windows on the south side are certainly also a novelty. Hammams – for obvious reasons – had no windows at all or had very small windows.

It seems that my bath was not internally divided, it consisted of only one part, the so-called hot part. There was also no room in it, which we would call a changing room today. This function was fulfilled by the courtyard surrounded by a wall, almost the same area as the interior, especially since the still standing columns around could easily be used to support a light roof, protecting from the sun and unauthorised eyes.

The new floor tiles on the entire surface certainly make it impossible to investigate the details of the hydraulics, i.e. the water circulation in Velia Pasha’s hammam. It is certain, however, that the toilet part (WC) of the bath was located in exactly the same place as my modern bathroom, on a slight elevation, on the north side. Perhaps there was also a drain for the entire hammam.

I wonder if I should thank the Muslim hammam for the idea of a flowing water instead of a swimming pool? Is it because of this that, despite living in a former bathhouse, I have a very dry interior, without the humidity so common in Greek houses?

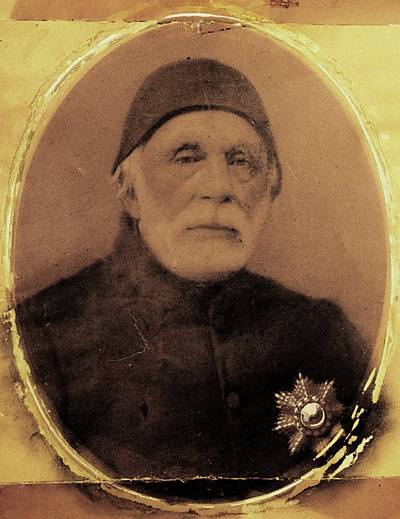

Mustafa Naili Pasha

Giritli (Cretan) Mustafa Naili Pasha was the father of Veli Pasha, who built the house in which I live in 1852. His person is a great example of the tangled fates of people, the ambiguous ethnic identities and the incredible cultural mix, so characteristic of ancient Crete, and increasingly being removed from the collective consciousness today.

Mustafa Naili was born in 1798 in the small village of Polyen on the northwestern borders of the Ottoman empire. Today, this town is called Pojan, located in eastern Albania, 8 km from Lake Prespa. However, already in his early childhood, Mustafa spent several years in Egypt, and in 1809 his uncle sent him to Hijaz, a province in present-day Saudi Arabia. Mustafa spent 10 years there, during which time he was in the service (or rather, in the upbringing, due to his young age) of Mehmet Ali, the ruler of Egypt, who also came from Albania.

In 1821, Mehmed sent Mustafa to Crete. For the first few years, he commanded the Muslim troops on the island, and later for many years he was governor of Crete, both on behalf of Mehmet, i.e. Egypt, and later on behalf of the Turkish sultan from Istanbul. He seems to have had no ethnic prejudices whatsoever. He tried to regulate Greek-Turkish relations, even establishing a Christian-Muslim council and hoping to gain the support of both main groups living in Crete in creating a kind of independence for the island. Unfortunately, widespread nationalism was already spreading to all corners of Europe and there was no chance for peaceful coexistence.

Mustafa Naili married Helena Bolanopoula, the daughter of an Orthodox priest, allowed her to remain a Christian, and the couple even had a small garden chapel in the Pasha’s residence in Perivoli near Chania. Helena was the mother of Veli Pasha (Mustafa – as an exemplary Muslim, he had several wives and many children). Mustafa Naili was considered the richest man in the Ottoman Empire. In 1851, the Sultan summoned our hero to Istanbul. Mustafa became a vizier (the most important official in the empire) and spent the last 20 years of his life at the Sultan’s court.

Greece is not blue...

Okay, but why is in the title of this essay the word “blue”? Does my house have any blue elements? Or more generally: despite its Turkish origins, are there any elements in my house that we would automatically recognize as Greek?

The association of Greece and the color blue is almost automatic. Not even because of the colors of the Greek flag, but because of the endless amounts of advertising images encouraging people to visit the country of Socrates and Plato. Also, the so-called “Greek style” in interior design is white with clear blue accents. However, nothing could be further from the truth than this stereotypical idea.

Greece is not blue at all. In stores with interior design – and there are hundreds of them in Chania – you will look in vain for anything that is blue. There are browns and beiges (dominant), reds, greens and yellows, but blue is rare. It is similar on the facades of houses. Generally, there are no white and blue houses in Crete – so obvious to a tourist. It is similar in Litochoro or Athens. Of course, it is a bit different on the Aegean islands or in some villages in Crete (e.g. Loutro), but these are just exceptions that prove the rule. Similarly to souvenir shops, where various blue trinkets are common and a tourist, confirmed in his stereotypical ideas, can easily buy them and take them home.

Tourist shops are a special case, since they even offer the head of Venus de Milo, Nike of Samothrace or the famous rhyton in the shape of a bull’s head from Knossos – all in blue, without any connection with the original appearance of these artifacts and without any sense. What’s more, the owner of one of these shops informed me that she has the same miniatures in several other colors, equally absurd and to the same extent devoid of any sense. But if the orange head of Venus de Milo will match the color of the curtains in the living room of an uncritical admirer of Greek beaches, then the skillful hands of Chinese manufacturers will do anything.

Gifts shop in Chania. Whatever you want in blue (and any other color you like)

…but tourists love the Aegean blue

But where does this incredible career of the color blue in (stereotypical) Greece come from? There are several theories on this subject, but none are particularly convincing. Certainly, the white-and-blue craze has nothing to do with Greek tradition, it was born quite recently – at the earliest between the First and Second World Wars – and became popular on the Aegean islands even later, in the 1960s and 1970s. It is easy to see this by looking at, for example, photos of Santorini from the 1950s – there are almost no white-and-blue houses on them, and the narrow streets-staircases are not painted white either!

It seems that the Greek Queen Frederica contributed greatly to the popularization of the new style. In 1954, she organized a cruise on the Aegean Sea for her (mainly crowned) friends, and showed several photos of the white houses of Mykonos to Prime Minister Konstantinos Karamanlis with the suggestion that such a style would be a great advertisement for Greece. A short while later, popular culture took over the marketing baton through its most important incarnation at the time, cinema. The film “Boy on a Dolphin” from 1957, starring Sofia Loren, shot on Mykonos, Rhodes and Hydra, documents all these islands with a certain amount of white and blue architectural elements, but they are not as dominant as they are today. A similar image is shown in Werner Herzog’s first feature film “Signs of Life” – (Lebenszeichen) shot on the island of Kos in 1968.

So what is Greece like if not white and blue? The walls of houses in many traditional regions – in the Pindos Mountains, in the Peloponnese (Mani) or on the Pelion Peninsula – are naturally stone (i.e. gray-brown) with small additions of natural wood (dark brown). In cities, various shades of cream, beige, brown and even muted pink predominate on the facades of buildings. The traditional Greek carpet – called flokati – is red. It has black, yellow and green patterns, but never blue.

Blue windows and doors

Returning to my new home. Are there any blue elements in it? Not much. However, both in Veli Pasha’s former hammam and in my two neighbors’ flats, the windows and doors are painted blue. This is not entirely orthodox, since the external walls are not white at all. It is also very likely that this blue is a remnant of the period when these apartments were rented to tourists for short-term stays. However, since I already have something blue, I decided to paint the legs of my work table in the color of the sky, I also have two blue pillows and a similar color bedspread.

However, I will not buy a blue Venus de Milo head for myself.

Litochoro and Chania – my two places in Greece

Finally, my new home from a slightly broader perspective. Instead of analyzing every stone in my garden, I will try – like the hero of Selma Lagerlof’s book – to rise up and instead of the details see the overall picture: Halepa – Chania – Crete – Greece. What delights me and why am I here?

I have been living in Greece for five years. Three years in Litochoro near Olympus, the last two in Chania. The list is not entirely precise, since I spend many months (!) of each year traveling. I have lived in several places in the town near Olympus, but I would not call any of them home, for various reasons. However, comparing these two places may be interesting. Litochoro vs. Chania – what are the similarities and differences?

The main reason for the decision to live in Greece was the desire to explore, to get to know new places. Both the different cultural layers of ancient and more modern Hellas, as well as the mountains and wildlife. And if Litochoro and its surroundings offered relatively little in terms of culture (for Greece), the richness of Crete in this regard is absolutely incredible, even on a European scale. When it comes to nature and mountains, although the expression “wild nature” describes both places well, there are probably no two mountains in Greece as different as Olympus and Lefka Ori, to mention only the vast forests on Olympus and their almost complete absence in Crete or the huge differences in climate.

Amazing Cretan culture...

Walking the streets of Chania, I constantly pass the remains of the Minoan culture, which are 5 thousand years old. The whole of Crete is a great book of Greek mythology and history. Running along the southern coast from Agia Roumeli to Sougia, I pass the cave where Polyphemus imprisoned Odysseus and his companions, and later threw large boulders towards their ship. In the palace of Knossos I imagine Theseus receiving a ball of thread from Ariadne and preparing to enter the labyrinth. And yet somewhere nearby there must be the rock from which Icarus took off on his last flight, and a little further southwest on the Nida plateau, right next to the path to Psiloritis is the cave in which Zeus was born. Every time I look with delight at the treasures of Minoan culture gathered in the Archaeological Museum in Heraklion, because they are one of the most brilliant achievements of the human imagination. And all this is just the beginning… How many times, sleeping in the tavern of Agios Pavlos, deserted out of season, have I imagined that this was the place where the ship carrying St. Paul to Rome was wrecked? How many times have I asked myself how it was possible to build the city of Lissos (3rd century BC) in such an inaccessible and rocky valley on the outskirts of Lefka Ori, with a still amazing view of the Libyan Sea? How dense with artifacts must this Island be if even the village where I quite accidentally appeared at a running competition turned out to be the birthplace of El Greco? How is it possible that after so many years and so many twists of history, the Venetian atmosphere of the streets of Chania is still easily felt? How is it possible that I accidentally live in a Turkish house built 170 years ago by the governor of Crete, who came from an Albanian-Christian family? The cultural richness of Crete is completely unbelievable, seducing every non-random explorer.

Wild landscape of the White Mountains in Crete. No paths.

... and advanced level of wilderness

It is similar with nature. On Olympus I was delighted by the existence of almost forgotten, unused paths, sometimes bringing them back to life. It was an incredibly exciting exploration, but mostly on paths (with perhaps the only long-distance exception – the 55 Peaks Project). In the White Mountains in Crete – the place of my constant admiration for nature – there are almost no paths at all, and exploring these mountains often involves hours of struggling through a stone jungle, with prickly fregana thickets, with no guarantee that you will reach a safe place before nightfall. What’s more, even if there are paths, they are nothing like those on Olympus. The amount of stones of all kinds, the much higher temperature, the almost complete lack of forests and even trees, and therefore shade, and the absolute lack of water make even moving along “clear” paths an adventure of a lifetime. This is why the 55 Peaks on Crete Project – despite being created on the map almost two years ago – has not yet been implemented. It is much more difficult on Crete than on Olympus.

So can there be a better place to explore than Crete? The question is of course rhetorical. My new blue house in Crete has a bright future ahead of it.

Chania – Halepa – Tabakaria, April 2025

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

Phaistos Disk. The messenger of the forgotten world

READ MORE

Zvara. About music, dance, Zagori Races and cosmic religion of Greece

READ MORE

Glistrokoumaria - Greek Strawberry Tree

READ MORE